Paris, Campus Condorcet, 12 octobre 2024

(English version below)

Le Xe siècle, pendant un temps considéré comme un « siècle de fer » par l’historiographie, a fait l’objet de multiples réévaluations depuis le début du XXIe siècle. Du point de vue de la production manuscrite cependant, le Xe siècle apparaît comme un parent pauvre du Moyen Âge. Reconsidérant cet apparent déclin, les récents travaux interrogent les transmissions et les transformations des pratiques manuscrites carolingiennes, montrant au contraire le renouveau des codices au Xe siècle[1]. Des grands centres carolingiens comme Saint-Gall, Reims, Auxerre, Fleury ou encore Ratisbonne copient de nouveaux textes et insèrent de nouveaux commentaires et de nouvelles gloses dans les manuscrits. La production manuscrite s’accentue aussi dans des espaces périphériques comme le nord de l’Espagne et le sud de l’Angleterre.

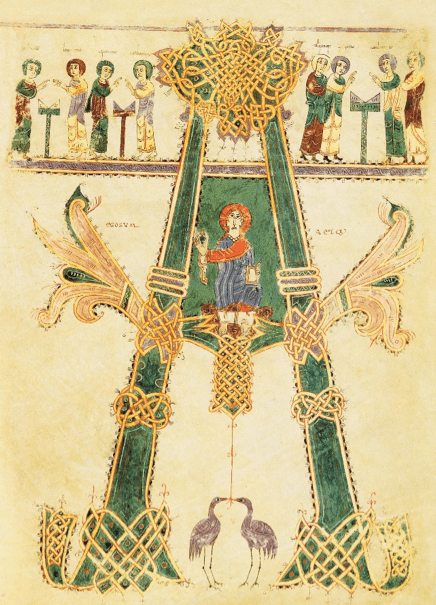

En outre, cette production manuscrite n’a encore que peu été étudiée sous l’angle du genre, sans doute en raison du déclin des monastères féminins à partir de la fin du IXe siècle. Pourtant, certaines institutions féminines, notamment en Saxe ottonienne, continuent d’être des lieux de copie et de production écrite : c’est à Gandersheim que Hrotsvita compose ses poèmes, ses drames et ses œuvres historiques. Mais elle n’est pas seule : dans le royaume de León, Ende réalise les centaines de miniatures du Beatus de Gérone. Le psautier perdu de la reine Emma témoigne aussi de la commande et de la possession de manuscrits. Dans l’Europe du Xe siècle, les femmes composent, copient, possèdent et utilisent les codices.

Le but de cette journée d’étude est donc de proposer une réflexion sur l’articulation entre les manuscrits du Xe siècle et le genre. L’approche sera résolument comparatiste : toute l’Europe de l’Ouest pourra être traitée, y compris des régions parfois encore considérées, à tort, comme marginales, à l’instar de l’Espagne ou de l’Angleterre. La borne chronologique du Xe siècle ne doit pas être comprise de façon restrictive et peut inclure les décennies précédentes et le début du XIe siècle.

Dans cette perspective, les participant‧e‧s sont invité‧e‧s à réfléchir autour de plusieurs axes :

– La production, la diffusion et les réseaux de circulation des manuscrits. Les institutions masculines et féminines prennent-elles part de la même manière à la copie des manuscrits au cours du Xe siècle ? La forme prise par les manuscrits est-elle différente ? Les institutions féminines insèrent-elles dans les mêmes réseaux de production et de diffusion des codices ? Les femmes s’inscrivent-elles dans les mêmes réseaux de lettré·e·s que les hommes ?

– Les œuvres lues et la literacy. Est-ce que les hommes et les femmes lisent les mêmes choses ? Leurs usages des manuscrits diffèrent-ils ? Quels est leur rapport à l’écrit ? La question vaut tant pour le latin que pour les langues vernaculaires, précocement écrites en Angleterre par exemple, et pour l’accès au grec.

– La mise en scène dans le manuscrit. Les hommes et les femmes se mettent-ils en scène de façon similaire à travers les manuscrits ? Les colophons et, partant, les copistes ont-ils recours aux mêmes tropes et aux mêmes techniques ? Les inscriptions marginales ou non révèlent-elles des dynamiques genrées ?

– L’auctoritas. L’auctoritas est-elle genrée ? Les femmes sont-elles en marge ? En quoi la réception des œuvres féminines est-elle différenciée au Xe siècle ? La conservation et la transmission des œuvres féminines dépend-t-elle d’un critère genré ?

Les propositions de communication, en français ou en anglais d’une page maximum, doivent être envoyées avant le 22 janvier 2024 à justine.audebrand@univ-poitiers.fr et julie.richard-dalsace@univ-paris1.fr.

Comité d’organisation :

- Justine Audebrand, ATER en histoire médiévale, université de Poitiers

- Julie Richard Dalsace, ATER en histoire médiévale, université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne

Comité scientifique :

- Paul Bertrand, Université Catholique de Louvain

- Geneviève Bührer-Thierry, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne

- Sylvie Joye, Université de Lorraine

- Octave Julien, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne

[1] Warren Pezé (éd.), Wissen und Bildung in einer Zeit bedrohter Ordnung. Knowledge and Culture in Times of Threat: The Fall of the Carolingian Empire (ca. 900), Stuttgart, Hiersemann, 2020 ; Beatrice E. Kitzinger et Joshua O’Driscoll (éd.), After the Carolingians. Re-defining Manuscript Illumination in the 10th and 11th Centuries, Berlin, De Gruyter, 2019 ; Sarah Louise Greer, Alice Hicklin et Stefan Esders (éd.), Using and Not Using the Past after the Carolingian Empire, c. 900 – c. 1050, Abingdon, Routledge, 2019.

Gender and Manuscripts during the 10th Century

Paris, Campus Condorcet, 12th of october 2024

(English version)

For a long time, historians considered the tenth century to be an “iron century”. But since the beginning of the 21st century, it has been the subject of numerous re-evaluations. Considering the manuscript production, however, the tenth century still appears to be understudied. Recent research examined the transmission and transformation of Carolingian manuscript practices and showed on the contrary the revival of codices in the tenth century. Major Carolingian centres such as St Gallen, Reims, Auxerre, Fleury and Regensburg copied new texts and inserted new commentaries and glosses into manuscripts. Manuscript production also increased in peripheral areas such as northern Spain and southern England.

Moreover, this manuscript production has not yet been studied from a gender perspective, perhaps because of the decline of women’s monasteries from the end of the ninth century onwards. However, certain women’s institutions, particularly in Ottonian Saxony, continued to be places of written production: Hrotsvita composed her poems, dramas and historical works at Gandersheim. But she was not alone: in the kingdom of León, Ende produced hundreds of miniatures for the Beatus of Girona. The lost psalter of Queen Emma also bears witness to the commissioning and possession of manuscripts. In 10th-century Europe, women composed, copied, owned and used manuscripts.

The aim of this workshop is therefore to explore the relationship between tenth-century manuscripts and gender. The approach will be resolutely comparative: the whole of Western Europe may be covered, including regions that are still sometimes wrongly considered to be marginal, such as Spain or England. The 10th century should not be understood restrictively and may include the preceding decades and the beginning of the 11th century.

Participants are invited to reflect on several axes:

– The production, distribution and circulation networks of manuscripts. Did male and female institutions took part in copying manuscripts in the same way during the 10th century? Were the forms taken by the manuscripts different? Were they part of the same production and distribution networks? Were women part of the same networks as men?

– Reading and literacy. Did men and women read the same things? Did they use manuscripts differently? What was their relationship to the written word? This question applies to Latin as much as to vernacular languages, written at an early stage in England, and to access to Greek language.

– Portraying inside the manuscripts. Did men and women portray themselves in similar ways in manuscripts? Did colophons and, by extension, copyists use the same tropes and techniques? Did marginal or non-marginal inscriptions reveal gendered dynamics?

– Auctoritas. Was auctoritas gendered? Were women on the margins? How did the reception of women’s works differ in the 10th century? Did the conservation and transmission of women’s works depend on gendered criteria?

Proposals for papers, in French or English and no longer than one page, must be sent by 22 January 2024 to justine.audebrand@univ-poitiers.fr and julie.richard-dalsace@univ-paris1.fr.

Organizers:

- Justine Audebrand, lecturer, Université de Poitiers

- Julie Richard Dalsace, lecturer, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne

Scientific commitee :

- Paul Bertrand, Université Catholique de Louvain

- Geneviève Bührer-Thierry, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne

- Sylvie Joye, Université de Lorraine

- Octave Julien, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne

Bibliographie indicative

Selective bibliography

I/ Manuscrits et genre / manuscripts and gender

Beach Alison, Women as Scribes: Book Production and Monastic Reform in Twelfth- Century Bavaria, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2004

Bodarwé Katrinette, Sanctimoniales litteratae: Schriftlichkeit und Bildung in den ottonischen Frauenkommunitäten Gandersheim, Essen und Quedlinburg, Münster, Aschendorff, 2004.

Bosseman Gaëlle, « Femmes et memoria liturgique dans la péninsule Ibérique (Xe-XIIIe siècle). Une approche à partir des Beatus », Médiévales, 80, 2021, p. 119-135

Goullet Monique, La femme et l’écriture au Moyen Âge, Auxerre, Musée Abbaye Saint Germain, 1998.

Le Nan Frédérique, Poétesses et escrivaines en Occitanie médiévale. La trace, la voix, le genre, Rennes, PUR, 2021.

Saunders Corinne, Watt Diane (éd.), Women and Medieval Literary Culture. From the Early Middle Ages to the Fifteenth Century, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2023.

II/ Manuscrits au Xe siècle / manuscripts during the 10th century

Greer Sarah L., Hicklin Alice et Esders Stefan (éd.), Using and Not Using the Past after the Carolingian Empire, c. 900 – c. 1050, Abingdon, Routledge, 2019.

Kitzinger Beatrice E. et O’Driscoll Joshua (éd.), After the Carolingians. Re-defining Manuscript Illumination in the 10th and 11th Centuries, Berlin, De Gruyter, 2019.

Pezé Warren (éd.), Wissen und Bildung in einer Zeit bedrohter Ordnung. Knowledge and Culture in Times of Threat: The Fall of the Carolingian Empire (ca. 900), Stuttgart, Hiersemann, 2020.

Vous devez être connecté pour poster un commentaire.